Lessons from disaster (I): History and Tokyo’s precarious circumstance

2025 marks three decades since Kobe, Osaka and the surrounding region in western Japan were rocked by the 1995 Kobe Earthquake, and 14 years since the quake, tsunami and nuclear disaster of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which occurred off the Pacific coast of Japan’s northeastern Tohoku region. Professor Kimiro Meguro, dean of the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies and Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies and editor of the book The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake Disaster and the University of Tokyo, published in 2024, explains how we can learn from the past to prepare for future disasters.

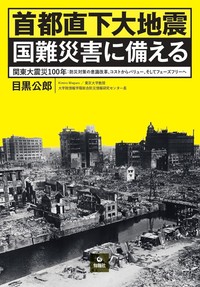

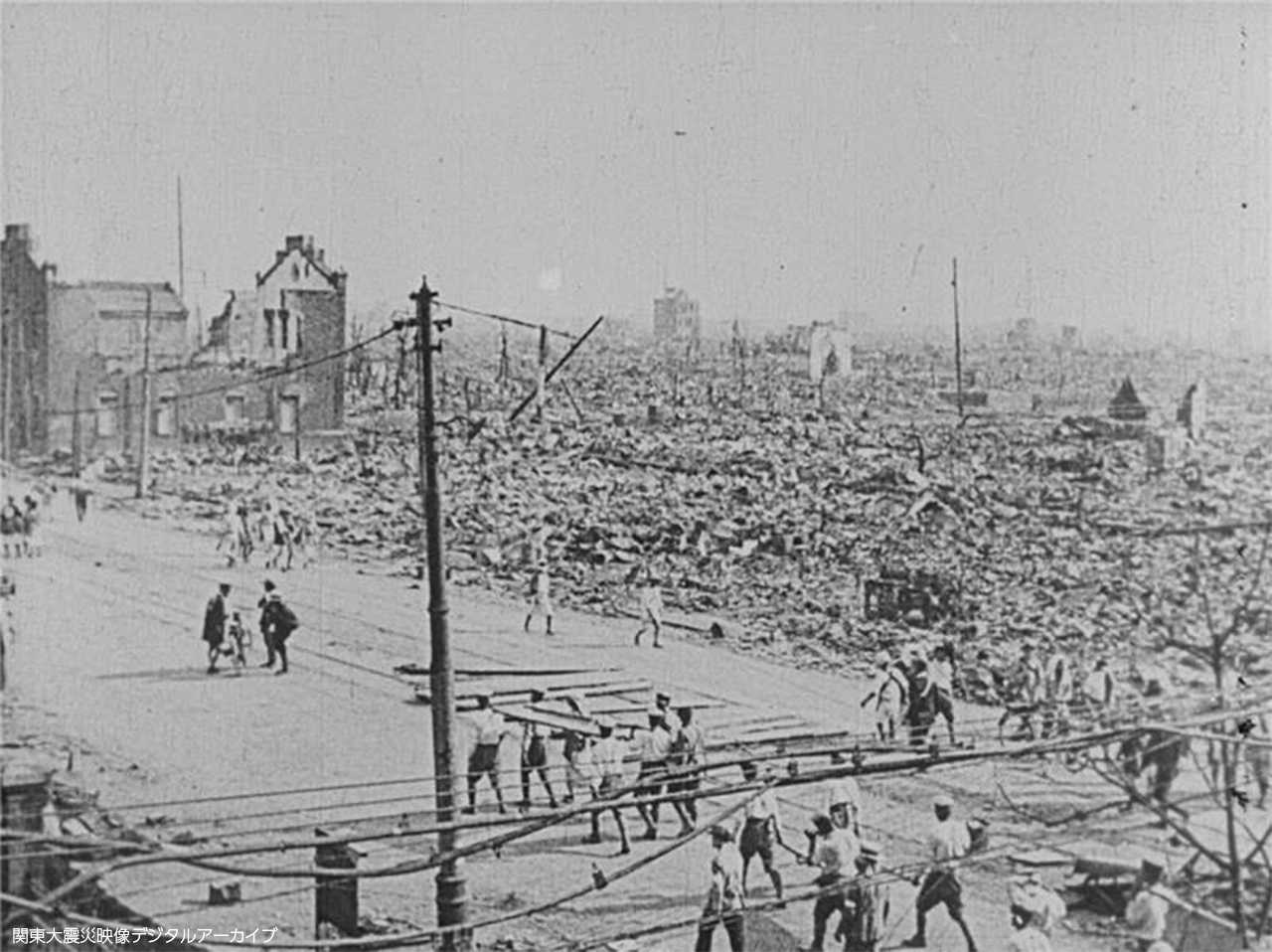

Source: The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 [Restored Version] from the films of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 Digital Archive (website for films held by the National Film Archive of Japan related to the Great Kanto Earthquake, a joint research project of the National Film Archive of Japan and the National Institute of Informatics).

Used with permission from the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 Digital Archive.

UTokyo’s disaster research

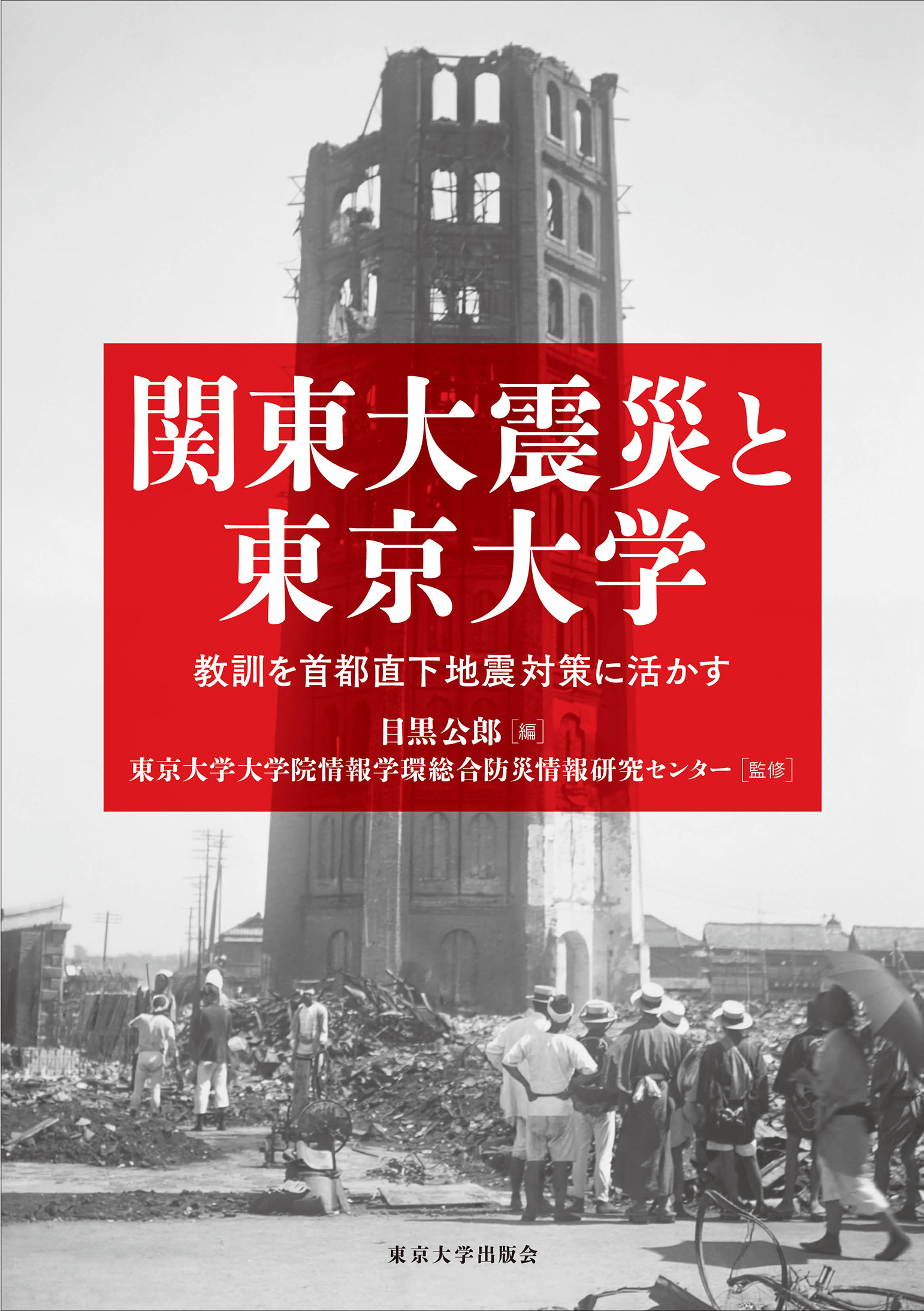

―― The book you edited on the University of Tokyo’s response and contributions in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and lessons to be learned for the next great earthquake was published last year. How has research on disaster here at UTokyo developed over time?

When we look at the database of research papers and materials, we can see certain trends in disaster research here at the university. Until around the 1940s, most research focused on what could be considered “hard” topics, like the physical mechanisms that underlie earthquakes and structural damage, and the related response. However, after baseless rumors resulted in the persecution of members of the Korean and Chinese communities following the Great Kanto Earthquake, we begin to see some studies that examine so-called soft topics related to social issues, such as the effect of disinformation. Then, after the 1995 Kobe Earthquake, research on disaster preparedness, recovery and reconstruction also increased. Research in recent years has expanded to include not only earthquakes, but also other natural disasters, such as volcanoes, storms and floods, as well as man-made disasters, such as terrorism.

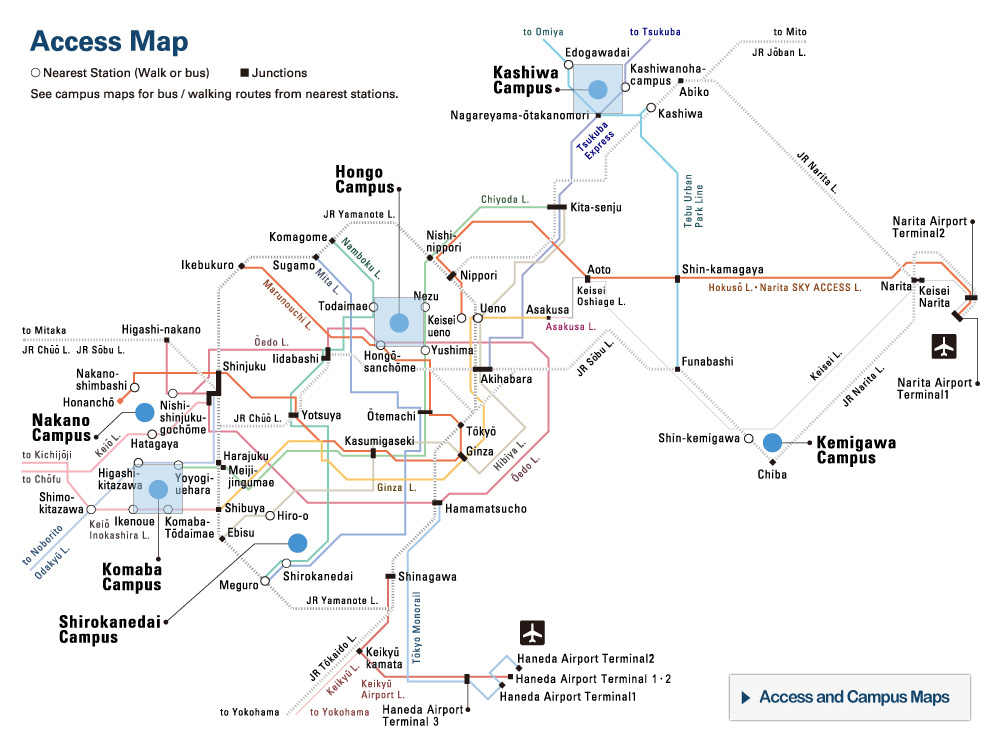

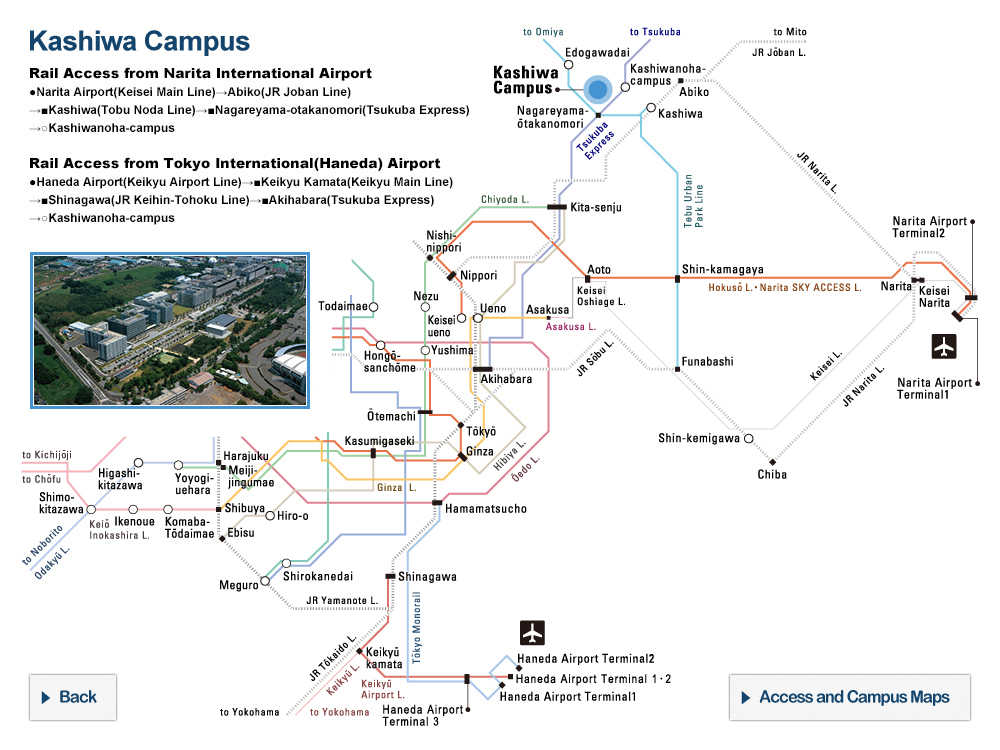

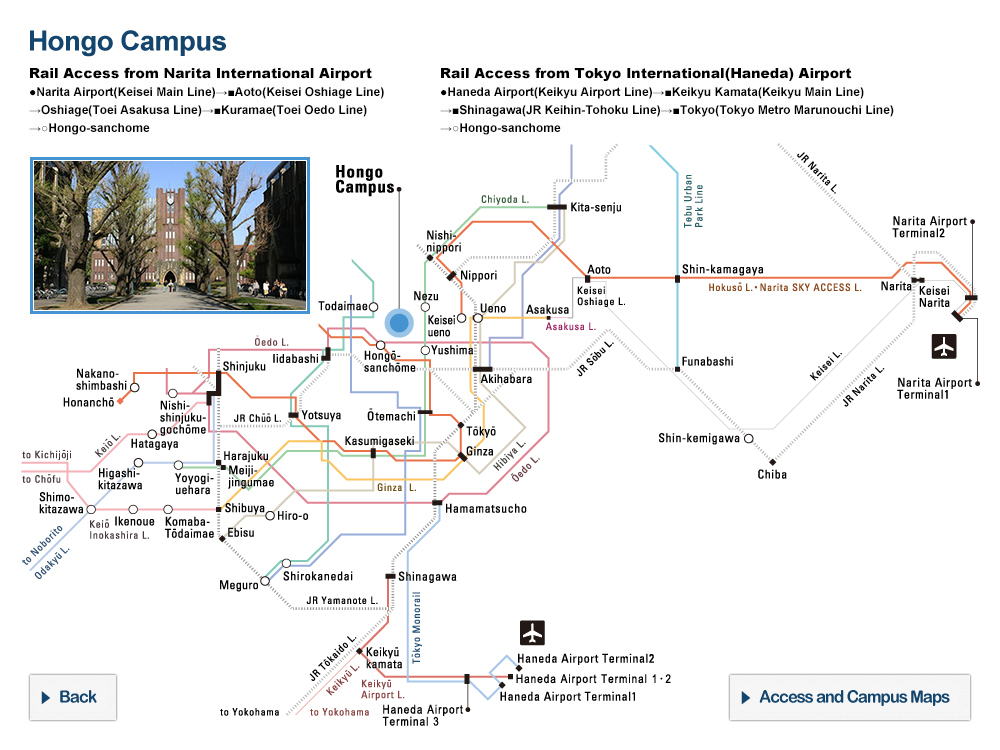

There have also been developments in interdisciplinary research. One example is UTokyo’s Center for Integrated Disaster Information Research, which was established jointly in 2008 by the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies, the Earthquake Research Institute and the Institute of Industrial Science to promote disaster research that combines the humanities and sciences. Another example is the UTokyo Research Initiative for Disaster Management and Reconstruction, a universitywide effort founded in 2021 to support comprehensive research on disasters, disaster management and reconstruction. Led by this collaborative initiative, researchers of disaster prevention at the University of Tokyo gathered in 2023, the 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake, for a symposium series at Yasuda Auditorium in the Hongo Campus. The insights and outcomes of the symposium were compiled and published in 2024 as the edited volume The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake Disaster and the University of Tokyo.

The politics of disaster

―― The book discusses a connection between political movements and large-scale disasters. Can you tell us what occurred in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake?

Before the earthquake, Japan was in the midst of the Taisho Democracy period, in which society as a whole was moving toward broader representational government. This included the transition from the oligarchic rule of the Meiji period (1868-1912) to party politics, as well as the emergence of movements advocating for constitutional protection, labor, women’s suffrage and Buraku liberation (fighting to eliminate discrimination against Japan’s outcast minority population). Western-style food, clothing and housing were introduced into people’s daily lives, and a new urban culture was blossoming in metropolitan areas. And during World War I, from 1914 to 1918, Japanese products were experiencing a boom overseas, and Japan’s economy flourished.

After the end of World War I, however, Japan fell into a postwar recession, and from 1918 to 1921, the Spanish flu pandemic swept the country, infecting approximately 24 million people, or 44% of Japan’s population at the time, and killing 390,000. It was during this period that the Great Kanto Earthquake struck. Tokyo suffered extensive damage, and its recovery and reconstruction became a top priority for both the government and the people. These required strong leadership, as well as certain restrictions on private rights. The government issued an emergency imperial ordinance in 1923 to maintain public order in the chaos that followed the earthquake. The ordinance was supplanted in 1925 by the Peace Preservation Law, which was used to crack down on movements that rejected Japan’s national polity and private property system. For businesses that struggled to repay loans due to the earthquake, the government implemented measures, such as declaring a moratorium on repayment and issuing discounted earthquake bills, which compensated a certain amount of debt. However, these measures resulted in bad debts, which triggered a financial crisis in 1927.

In the years that followed, Japan experienced the Showa Depression of 1930; the Manchurian Incident of 1931 (leading to Japan’s invasion and occupation of the region in northeastern China); the May 15 Incident of 1932 (an attempted coup in which the prime minister was assassinated); withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933; the February 26 Incident of 1936 (a second coup attempt); and the Second Sino-Japanese War, which broke out in 1937, and ultimately the Pacific War, which the country entered in 1941. And in 1945, 22 years after the Great Kanto Earthquake, Japan faced defeat in World War II and the loss of 3.1 million lives, including civilians. The measures the government implemented with the intention of benefiting the greater good and which the people supported, backfired, and before long, the nation had drifted toward totalitarianism.

Considering that now, three decades have passed since the 1995 Kobe Earthquake and 14 years since the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, it is clear how drastically society has changed since the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Defeat in World War II marked the midpoint of the 156 years since the end of the feudal period, which ushered in the Meiji Restoration, and 2023, the 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake. Japan was profoundly affected by its defeat in World War II, and although the nation had since moved forward, it is important to remember that the effects of the Great Kanto Earthquake 22 years prior lingered in the background of that period.

―― How do you view the current situation in Japan, 14 years after the Great East Japan Earthquake?

In order to prevent catastrophic damage from future major earthquakes, we need to prepare countermeasures ahead of time based on what we learned from the Great Kanto Earthquake disaster over a century ago and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake disaster. Although it will likely be more than 100 years before we see another magnitude 8 megaquake along the Sagami Trough, southwest of Tokyo, which ruptured during the Great Kanto Earthquake, there is a high possibility of the Tokyo Metropolitan Inland Earthquake or the Nankai Trough Earthquake — along an ocean-floor trench off the southern coast of Japan — within the next few decades. Given this situation, discussion on preparation of disaster management at the national level is essential.

We need to simulate an accurate picture of how society will change 10, 20, 30 years from now, in terms of population, age distribution, percentage of foreign residents, industrial structure and aging infrastructure. We must then assess what kind of damage could occur, and to what extent, if an earthquake were to strike at any given time. This includes anticipating what subsequent issues could emerge over time, and what measures — including legislation — need to be put in place in advance to improve and resolve those issues. We must also estimate how much time such measures would take and begin implementing strategies via backcasting, wherein we plan backward from the future in order to avoid being caught off guard. However, discussions like these are virtually nonexistent at present — instead, what we see are discussions that are overly focused on short-term troubleshooting. There is an overwhelming lack of effort to take a broader perspective, anticipate future events, and take the appropriate proactive measures.

Formulating and implementing the appropriate measures require that we constantly employ two yardsticks, used to calculate on either a macro or micro scale. One is for gauging large spaces and long spans of time, while the other is used to measure smaller spaces and shorter periods of time. The former provides a long-term perspective on the direction the nation should take, while the latter demonstrates specific actions and their effects from the perspective of the people. Although it is important for many people to use the latter micro yardstick to identify optimal local solutions, focusing solely on this approach risks losing sight of the broader direction that we need to take as a whole.

Hyperconcentration in Tokyo

―― What is something we learn by taking a long-term perspective of Japanese history?

Taking a long-term perspective reveals the fundamental causes of various problems. For example, the problems posed by the heavy concentration of the population, government function and wealth in the Tokyo metropolitan area can be traced back to the Edo and Meiji periods. During the Edo period (1603-1867), the daimyō (feudal lord) of each domain had to travel back and forth between the capital Edo (present-day Tokyo) and their home domains once per two years in large processions while their principal wives and legitimate children had to live in Edo as hostages. This system, known as sankin-kōtai, was established in 1635 by the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu as a means of preventing rebellion against the shogunate, as the high costs of these large processions were borne by the daimyō themselves, making it difficult to accumulate wealth. That is the general understanding of raison d’être given for the system, but in reality, the reasoning behind this system changed significantly early on in its implementation. Based on the first volume of a collection of regulations called Kanpō Shūsei, issued between 1615 and 1743, we know that the shogunate felt that the size of the processions and the number of attendants had grown excessive, which was both a waste in terms of governing the domain and a burden on the people, and the shogunate commanded that the number of attendants be reduced according to the daimyō’s standing. If the intent of sankin-kōtai was to prevent the accumulation of wealth, an edict showing concern for the cost of these processions would be quite unusual.

Another facet of the sankin-kōtai system that is contrary to popular belief is its contributions to the development of national infrastructure. These large processions led to the improvement of roads and roadside post towns, as well as some waterways, which greatly revitalized the flow of goods throughout the country and increased GDP. The sankin-kōtai system also contributed to human resource development on a national level. The system periodically exposed the most talented individuals from the domains whom the daimyō surrounded themselves with, to Edo, the most scientifically and culturally advanced place in Japan; moreover, as the domains were engaged in similar activities in the capital, the talented individuals gathered there from the provinces were able to build networks in Edo. While as people were registered with their domains, their children were born and raised in their respective domains, and educated in the domain’s schools; however, exceptionally talented children were given the opportunity to study at superior schools in other domains, thanks to the networks their fathers had built in Edo. In this way, the sankin-kōtai system played a significant part in the longevity of the Edo shogunate while also preventing decline in the provinces.

The Meiji government, meanwhile, rounded up talent who had been nurtured back home in the provinces during the Edo period, and gathered them in Tokyo in one fell swoop. They were made to study with foreign nationals and sent abroad, and upon their return, placed in key government and administrative positions. As a result, Japan was able to catch up with the world’s most advanced nations in just 30 years after the dawn of the Meiji Restoration, when a new government was established under imperial rule in 1868. The fact that most of the Japanese researchers who had achieved world-class research outcomes around 1900, as well as most of the leaders of academic organizations in Japan, were from outside the Tokyo metropolitan areas attests to this reality. Japan was able to achieve such miraculous development because of such talented individuals, but the Meiji government failed to establish a system to redistribute talented individuals back to the provinces. I believe that this is the primary cause of regional decline.

―― How is the hyperconcentration of function and the population in the Tokyo metropolitan area currently manifesting itself as a problem in Japan?

The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake made apparent the shortage of manpower in provincial municipal governments. For example, the number of municipalities, which serve as the primary base of local government, decreased from approximately 3,400 to 1,700 between 1999 and 2010, due to a large number of mergers among cities and towns. And these mergers are thought to have increased the overall size of the affected municipalities as a result. However, when sorted by population size, more than 85% of municipalities nationwide have a population of 100,000 or less, 53% number 30,000 or fewer, and for 30%, 10,000 or smaller. The number of administrative staff in municipal governments is approximately 1 per 100 residents, but because the kinds and quality of services offered by local governments should be the same regardless of population size, smaller municipalities must manage the same range of tasks with fewer staff.

Left: Workers from Nagoya assist with supply delivery in the city of Nanao, Ishikawa Prefecture.

Right: Staff from Aichi Prefecture and elsewhere support the operation of an evacuation center in the town of Shika, Ishikawa Prefecture.

Source: Daikibo saigaiji ni okeru chiho kokyodantaikan no shokuin haken (“Dispatch of staff among local governments in time of large-scale disaster”), Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, August 2024 (Japanese)

Currently, more than 450 municipalities lack specialized staff in departments responsible for disaster response, including disaster and crisis management. In other words, these tasks are handled by staff who also have to perform other duties. Under such circumstances, what would happen to a small municipality in the event of a major disaster? Although the number of disaster victims may be limited due to the small population, from the perspective of emergency responders and other help, aiding the same 100 victims is more difficult when they are widely dispersed than when they are concentrated in one area. Geotechnical disasters, slope failures and infrastructure damage are more likely to occur over a wide space, making it difficult for municipalities with a large area relative to their population to respond effectively. Moreover, in addition to the initial emergency response following a disaster, departments overseeing disaster response and construction work in affected areas must also handle recovery and reconstruction projects that cost several times the normal annual budget of the whole municipality, which naturally leads to problems. While disaster response led primarily by municipalities, as stipulated in Japan’s Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act, is unlikely to improve in the future, the challenges it faces are only expected to grow.

(First of a two-part story. Continues in "Lessons from disaster (II): Disaster preparation for all circumstances.")

Kimiro Meguro

Dean and professor, Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies and the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies

Received Ph.D. degree from the Graduate School of Engineering at UTokyo. Professor in the Institute of Industrial Science (IIS) at UTokyo since 2004 after working as a research associate, then associate professor at IIS. Served as director of the International Center for Urban Safety Engineering at IIS from 2007 to 2021. Professor in the Center for Integrated Disaster Information Research at the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies (III) since 2010, serving as its director from 2021 to 2023. Appointed and serving as dean of the III and the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies (GSII) since 2024. Author of numerous publications, including Shuto Chokka Daijishin Kokunan Saigai ni Sonaeru (“Preparing for a National Critical Disaster like the Tokyo Metropolitan Inland Earthquake”) (Junposha, 2023), as well as the editor of The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake Disaster and the University of Tokyo: Lessons for the Next Great Earthquakes, such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Inland Earthquake (University of Tokyo Press, 2024).

Interview date: Jan. 21, 2025

Interview: Yuki Terada, Hannah Dahlberg-Dodd